Buying or selling a home often feels like navigating a maze of fees and taxes: lender fees, property taxes, down payments, inspections, commissions, and other closing costs. But depending on where the home is located and how much it sells for, there’s another charge that can catch even savvy buyers or sellers off guard: the mansion tax.

A mansion tax is a form of real estate transfer tax triggered when a property is sold above a certain price threshold. Despite its name, the tax doesn’t just apply to sprawling estates—it can affect even modest homes in high-cost housing markets. In New York City, for instance, a studio condo selling for just over $1 million is enough to activate the mansion tax.

Typically, the buyer pays this tax, calculated as a percentage of the home’s sale price. Rates and thresholds vary widely by location, with both statewide and local versions in effect across the U.S.

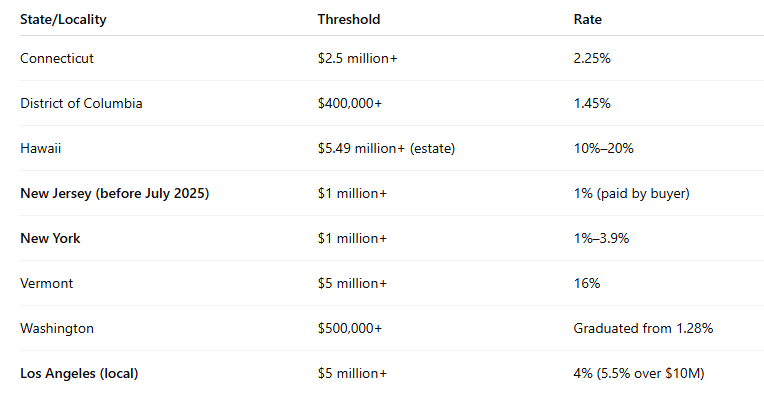

Here’s a snapshot of current mansion tax policies in select jurisdictions:

Note: Some jurisdictions have similar taxes under different names. For example, San Francisco’s real estate transfer tax uses higher rates for more expensive properties—effectively targeting high-value transactions without labeling it a “mansion tax.”

As property values climb in high-demand markets, mansion taxes are becoming an increasingly relevant concern—not only for homeowners, but also for corporate mobility programs assisting employees in buying or selling real estate during relocation.

Major Change in New Jersey’s Mansion Tax: What Mobility Teams Must Know

As of July 10, 2025, New Jersey enacted sweeping changes to its mansion tax, redefining who pays it and how much is owed.

Previously: The buyer paid 1% on homes above $1 million.

Now: The seller pays, and the tax is graduated:

- Transfers over $1million but not more than 2 million: 1%

- Transfers over $2 million but not more than 2.5 million: 2%

- Transfers over $2.5 million but not more than 3 million: 2.5%

- Transfers over $3 million but not more than 3.5 million: 3%

- Transfers above $3.5 million: 3.5%

Implications for Mobility Teams

Mobility teams will want to understand and consider how this could impact employees departing New Jersey. We expect to see:

- Increased seller costs: A $3.6M sale now incurs $126,000 in tax—more than triple the previous amount.

- Reduced home equity: Relocating sellers could lose a substantial portion of equity, potentially paying this tax when they bought and now when they sell.

- Pricing strategy shifts: Agents may advise listing just under the threshold amounts to reduce or avoid the tax.

Contracts executed before July 10 may still qualify for a refund if the property closes by November 15, 2025. Refund requests must be submitted within 12 months of deed recording, with proof of contract date.

Key Considerations for Mobility Programs

- The tax is not deductible for federal income tax purposes and will directly reduce net proceeds, impacting funds available for a down payment at the destination location.

- Encourage employees to check contract execution dates to determine refund eligibility.

- Agents and attorneys can help with strategic pricing, communicating seller obligations, and handling refund paperwork.

- Employees may request policy exceptions or financial support to offset this tax, especially if close to the thresholds. Decide in advance whether this is reimbursable under your program.

- If adjustments are made, update cost estimates and policy documentation accordingly.

- Without home sale benefits, employees may hesitate to sell—and therefore to fully commit to the new location—if they expect a possible return move.

Additional Cost Impact to Employers Using BVO/AVO

If your program includes a Buyer Value Option (BVO) or Amended Value Option (AVO), the cost shifts to the company. Because New Jersey treats these transactions as “one-deed” transfers (not requiring back-to-back closings), the employer is considered the seller—and thus responsible for the mansion tax.

And the impact could be steep for a mobility program. For companies offering a BVO or AVO, the revised mansion tax becomes a new relocation cost. Here are a few examples of what the cost could be:

- $1,250,000 sale is 1% = $12,500 mansion tax

- $2,000,000 sale is 1% = $20,000 mansion tax

- $2,000,001 sale is 2% = $40,000.02 mansion tax

Whoa, notice that the additional one-dollar just doubled the tax increasing the cost by $20,000.02

- $3,500,000 sale is 3% = $105,000 mansion tax

- But a $3,500,001 sale is 3.5% = $122,500.04 mansion tax

For mobility programs with frequent high-value sales in New Jersey, these changes represent a significant new cost line. Review budgets, consider home value caps, and adjust policies as needed.

The Reality

This change is projected to generate over half a billion dollars in new state revenue—but it also creates a financial hit for relocating employees (if uncovered) or for mobility programs that provide home sale support.

Whether your program covers these costs or not, expect increased pressure for exceptions, higher visibility of costs, and more complex negotiations. Clear communication and a proactive stance will help you navigate the shift.

For more details:

- Podcast: The Pulse and Perspective, July 3 - New Jersey Mansion Tax Shake-Up & Mid-Year Market Momentum

- Podcast: Brach Eichler Talks, NJ ‘mansion tax’ rates increase under new bill

- Article: Realtor.com, New Jersey Just Raised Taxes on Luxury Home Sales—Who’s Paying the Price Now?

/Passle/56686a093d94740bd0dda608/SearchServiceImages/2025-12-18-13-57-36-610-69440850c311190ddba29357.jpg)

/Passle/56686a093d94740bd0dda608/SearchServiceImages/2026-01-21-17-44-52-171-69711094b10160e443b3d133.jpg)

/Passle/56686a093d94740bd0dda608/SearchServiceImages/2026-01-09-19-58-54-377-69615dfeed0bb2914998d2fe.jpg)